The past few months our Textile Design Guide has been delving into the complicated and fascinating stories behind the fabric industry. In honor of Black History Month we’re spotlighting two of the many black artists, craftspeople, and laborers who have made contributions to the textile industry.

It’s important to note that the two stories we’re sharing survived the forgetful folds of history. The textile industry is indebted to the many black men and women whose work was often coerced and remains largely un-credited.

Today, we explore the historical legacy of two of America’s premier black textile artists. These two incredible women were born into slavery in the American South. Their work is on display in the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History.

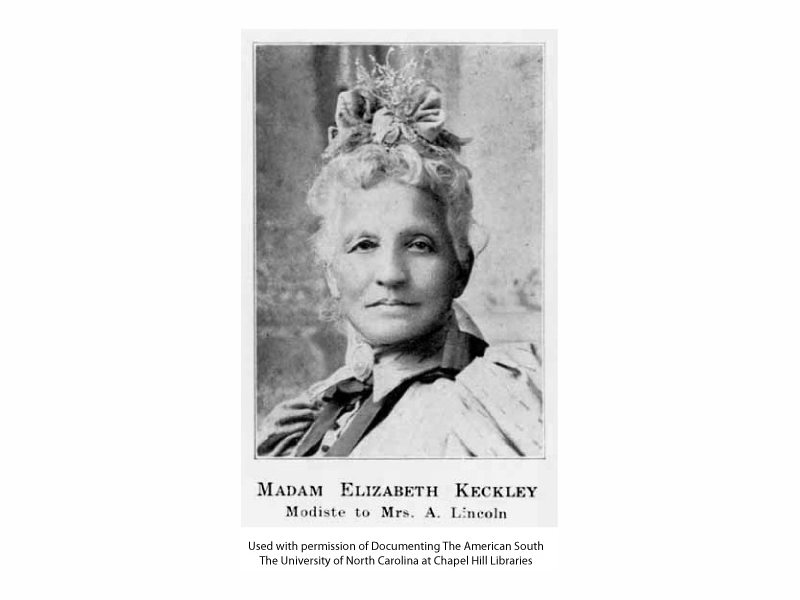

Elizabeth Keckley

Elizabeth Keckley, born in Virginia in 1818, is the ultimate embodiment of American entrepreneurship. Keckley used her dressmaking skills to buy her own freedom. After moving to Washington D.C. she became FLOTUS Mary Todd Lincoln’s personal designer and confidante. Society acclaimed her “perfect fit and skill with drapery.” Her celebrity patron is one reason rich, detailed records of her life exist. In 1868 she published her autobiography, Behind the Scenes: Or, Thirty Years a Slave and Four Years in the White House.

Two of Keckly’s stunning creations for the First Lady are viewable online in the Smithsonian’s archives, here.

Harriet Powers

Harriet Powers (1839-1910) grew up a slave in in rural where she was set free as a result of the American Civil War. There, Powers worked as a seamstress, primarily focusing on quilts. Using traditional applique techniques she crafted visual tales of Biblical events and celestial patterns. Powers’ story was recently documented in Dr. Gladys-Marie Fry’s work, Stitched from the Soul: Slave Quilts from the Antebellum South (2002). This book is one of the first efforts to research the enslaved quilting community.

Power’s Bible Quilt, above, is a stunning example of her work. This stitched artwork depicts Biblical scenes in a style you wouldn’t expect from a Southern quilter of the late 19th century.

Given the ephemeral nature of textile work, which is often subject to degradation, wear, and sometimes complete destruction, it is important to keep the stories of these women alive. Their art may not survive the ravages of time, but their stories should.

Learn more about black textile artists through history by checking out the quilt and dress collections at the new National Museum of African American History and Culture in D.C.

Leave A Comment